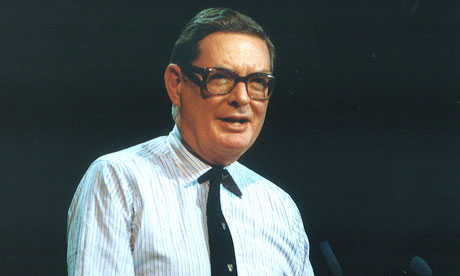

Sir Anthony Tennant was shipped in to clear up the mess at Guinness

When Sir Anthony Tennant, who has died aged 80, agreed to become chairman of Christie's International in 1993, he could never have imagined that his decision would mean him ending his life as a fugitive from justice, certain to be arrested if he ever set foot in the US.

Tennant embodied the world's idea of the patrician British gentleman. His father was from a wealthy, aristocratic Scots farming and military family, his mother was a viscountess. Born in London, he was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, and served in the Scots Guards in Malaya. During his working life he collected a knighthood (1992), a couple of honorary degrees and the Médaille de la Ville de Paris. He was a chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur. His upright, confident manner was reflected in his standing in the business community.

When he left the army at the age of 23, instead of going into the City, Tennant got a job with the then leading advertising agency in London, Mather & Crowther. He was fascinated by marketing, coming up with such slogans as "Schhh – you know who" for Schweppes and "Good Food Costs Less" for Sainsbury's, and stayed in that field for the next decade and a half. In 1970, he joined the brewing group Truman's, piloting the company through the merger with Watney Mann. In 1976, he was poached to become managing director and then chief executive of International Distillers and Vintners (IDV), where he remained until 1987.

There he was responsible for the launch of a number of innovative brands, transforming a mediocre spirits business into a global drinks group. However, he lost out in the contest for the top job at IDV's parent company, Grand Metropolitan. At about the same time, the Department of Trade and Industry, acting on a tip-off from the US department of justice following a plea-bargain from the insider-trader Ivan Boesky, began to investigate an illegal share support operation at Guinness, the brewing group.

As the degree of the share fraud began to unravel, Guinness's chairman, Ernest Saunders, was forced to resign, and Tennant was shipped in to clear up the mess, first as chief executive and then, from 1989, as chairman. He had the perfect combination of respectability and business nous for the Guinness job. What is more, he had the support of the City.

Along the way, he picked up a string of non-executive directorships including Forte, the catering group, the pharmaceuticals giant Wellcome, the Guardian Royal Exchange insurance company and a couple of banks, including the US bank Morgan Stanley. He was also well known and respected across the Channel, becoming a director of BNP Paribas and of the luxury goods and champagne group LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton of Paris. He was even a director of the London Stock Exchange and chairman of the Royal Academy Trust.

So how was it that, less than a decade later, he was indicted by a federal grand jury in Manhattan for allegedly fixing commission rates charged to sellers of fine art at auction? Things started to go wrong when, in May 1993, he agreed to become chairman of Christie's International, which, along with Sotheby's Holdings, dominated the world market in international fine-art auctions.

In the six years that followed, according to the US department of justice, the two auctioneers conspired to agree commission rates charged to sellers, thus depriving the sellers of the opportunity to negotiate rates. At the top of the conspiracy, it was alleged, were the chairmen of the two companies, Alfred Taubman at Sotheby's and Tennant at Christie's.

Tennant insisted from the start that he was innocent of any wrongdoing, claiming he was hired by Christie's to perform an ambassadorial role, hosting events and wooing clients, moving effortlessly through the higher social echelons of London, Paris, New York and Tokyo, winning business for the firm.

Tennant freely admitted that he had met Taubman, who was convicted in 2001, and subsequently sentenced to a year in jail. However, he always insisted that any price-fixing that went on was agreed by the two chief executive officers of the companies, without the knowledge of their respective chairmen.

It was Christopher Davidge, CEO of Christie's, who "blew the whistle" on the scheme, earning himself immunity from prosecution. Dede Brooks, CEO of Sotheby's, admitted guilt and escaped jail, being sentenced to home detention, probation and community service.

Tennant never returned to the US. In a letter to friends following his indictment, he said he would not return to "clear his name" because it would have meant staying there for months, "possibly years", incurring huge legal bills. He asserted that his indictment meant that he could not appear as a witness for Taubman, who was the department of justice's real target. Whether or not that is the case, there is no doubt that Tennant's absence weakened Taubman's defence.

So Taubman alone went to prison, fairly or unfairly, while Davidge enjoyed the fruits of a multi-million payoff from Christie's. Tennant, meanwhile, did not need a US court of law to declare his innocence or guilt. "I prefer", he wrote, "to rely on the recognition of my friends that I am innocent of these charges."

Although, following the indictment, he gave up most of his charity and public positions, he remained thoughout a valued trustee of Monument Trust, a Sainsbury family charitable trust, serving as chairman following the death of Simon Sainsbury in 2006. He resigned earlier this year because of ill heath.

Tennant married Rosemary Stockdale in 1954. She survives him, as do their sons, Christopher and Patrick.

• Anthony John Tennant, businessman, born 5 November 1930; died 4 August 2011

Tennant embodied the world's idea of the patrician British gentleman. His father was from a wealthy, aristocratic Scots farming and military family, his mother was a viscountess. Born in London, he was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, and served in the Scots Guards in Malaya. During his working life he collected a knighthood (1992), a couple of honorary degrees and the Médaille de la Ville de Paris. He was a chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur. His upright, confident manner was reflected in his standing in the business community.

When he left the army at the age of 23, instead of going into the City, Tennant got a job with the then leading advertising agency in London, Mather & Crowther. He was fascinated by marketing, coming up with such slogans as "Schhh – you know who" for Schweppes and "Good Food Costs Less" for Sainsbury's, and stayed in that field for the next decade and a half. In 1970, he joined the brewing group Truman's, piloting the company through the merger with Watney Mann. In 1976, he was poached to become managing director and then chief executive of International Distillers and Vintners (IDV), where he remained until 1987.

There he was responsible for the launch of a number of innovative brands, transforming a mediocre spirits business into a global drinks group. However, he lost out in the contest for the top job at IDV's parent company, Grand Metropolitan. At about the same time, the Department of Trade and Industry, acting on a tip-off from the US department of justice following a plea-bargain from the insider-trader Ivan Boesky, began to investigate an illegal share support operation at Guinness, the brewing group.

As the degree of the share fraud began to unravel, Guinness's chairman, Ernest Saunders, was forced to resign, and Tennant was shipped in to clear up the mess, first as chief executive and then, from 1989, as chairman. He had the perfect combination of respectability and business nous for the Guinness job. What is more, he had the support of the City.

Along the way, he picked up a string of non-executive directorships including Forte, the catering group, the pharmaceuticals giant Wellcome, the Guardian Royal Exchange insurance company and a couple of banks, including the US bank Morgan Stanley. He was also well known and respected across the Channel, becoming a director of BNP Paribas and of the luxury goods and champagne group LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton of Paris. He was even a director of the London Stock Exchange and chairman of the Royal Academy Trust.

So how was it that, less than a decade later, he was indicted by a federal grand jury in Manhattan for allegedly fixing commission rates charged to sellers of fine art at auction? Things started to go wrong when, in May 1993, he agreed to become chairman of Christie's International, which, along with Sotheby's Holdings, dominated the world market in international fine-art auctions.

In the six years that followed, according to the US department of justice, the two auctioneers conspired to agree commission rates charged to sellers, thus depriving the sellers of the opportunity to negotiate rates. At the top of the conspiracy, it was alleged, were the chairmen of the two companies, Alfred Taubman at Sotheby's and Tennant at Christie's.

Tennant insisted from the start that he was innocent of any wrongdoing, claiming he was hired by Christie's to perform an ambassadorial role, hosting events and wooing clients, moving effortlessly through the higher social echelons of London, Paris, New York and Tokyo, winning business for the firm.

Tennant freely admitted that he had met Taubman, who was convicted in 2001, and subsequently sentenced to a year in jail. However, he always insisted that any price-fixing that went on was agreed by the two chief executive officers of the companies, without the knowledge of their respective chairmen.

It was Christopher Davidge, CEO of Christie's, who "blew the whistle" on the scheme, earning himself immunity from prosecution. Dede Brooks, CEO of Sotheby's, admitted guilt and escaped jail, being sentenced to home detention, probation and community service.

Tennant never returned to the US. In a letter to friends following his indictment, he said he would not return to "clear his name" because it would have meant staying there for months, "possibly years", incurring huge legal bills. He asserted that his indictment meant that he could not appear as a witness for Taubman, who was the department of justice's real target. Whether or not that is the case, there is no doubt that Tennant's absence weakened Taubman's defence.

So Taubman alone went to prison, fairly or unfairly, while Davidge enjoyed the fruits of a multi-million payoff from Christie's. Tennant, meanwhile, did not need a US court of law to declare his innocence or guilt. "I prefer", he wrote, "to rely on the recognition of my friends that I am innocent of these charges."

Although, following the indictment, he gave up most of his charity and public positions, he remained thoughout a valued trustee of Monument Trust, a Sainsbury family charitable trust, serving as chairman following the death of Simon Sainsbury in 2006. He resigned earlier this year because of ill heath.

Tennant married Rosemary Stockdale in 1954. She survives him, as do their sons, Christopher and Patrick.

• Anthony John Tennant, businessman, born 5 November 1930; died 4 August 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment